This is a guest post by David Epstein.

Picture this: you are on a committee to hire a new CEO for a large, multinational firm. There are a number of qualified candidates, you are told, each of whom has many years of experience in the relevant field, and then you are handed a background folder on each of them. In the folder you find detailed statements of what they would like to do with the company if they are hired.

So far so good, but when it comes to the candidates’ histories, the folder talks only about their deep formative experiences from when they were children, along with some amusing anecdotes from their lives over the past few years. Nowhere, though, does it tell you how these candidates have actually performed in their professional careers. Have they been CEO’s before? If so, how did their companies do? What projects have they tackled in the past, and what were the outcomes? All excellent questions, but nothing in the files provides any answers.

This is the situation voters find themselves in every four years when choosing a president. They are told what policies the candidates promise to enact if elected, sometimes with an evaluation of how realistic and/or desirable those policies would be. But nowhere, for the most part, are they given the candidates’ backgrounds in jobs similar to the one they are running for. (An outstanding exception to this rule is Vox’s review of Marco Rubio’s tenure as Speaker of the Florida House of Representatives.)

The Task Ahead

Here, I will begin to remedy this gap by comparing the legislative records of the four candidates who have spent time in the Senate: Sanders, Clinton, Rubio and Cruz. Sanders has proposed a “revolutionary” set of reforms; how likely is he to be able to make them into policy? Clinton spent twice as long as a senator from New York than as Secretary of State, but somehow that chapter in her political history is rarely spoken about. Rubio and Cruz are newer to the Senate, Rubio more of an establishment legislative figure (at least at first), and Cruz more clearly ideological. Do either of them have histories of getting their policies passed? And yes, it’s true – Rubio and Cruz have now dropped out of the race. But a) they might still be on the ballot as VP candidates, and b) it is interesting to compare them with the Democrats, as explained below.

Now, no one set of measures can completely capture how well a legislator does their job. I’ll be examining statistics having to do with proposing, voting on, and passing legislation, which might be considered legislators’ core activities. But members of Congress also must spend time doing constituency service, sitting on committees and subcommittees, appearing in the media, and more. And, of course, what of the candidates who were executives (governors) previously — how should we measure their performance? This analysis isn’t meant to be the final word on the subject; rather, it should provide some interesting material to consider and, hopefully, open a wider discussion on assessing candidates’ qualifications for the presidency.

TL;DR: Clinton comes out looking good in terms of effectiveness and bipartisan cooperation, and Rubio does surprisingly well for his first term, sliding down after that. Sanders had a burst of activity from 2013-14, but his years before and after that aren’t very impressive. Cruz’s brief time in the Senate has been almost completely unencumbered by working to pass actual legislation.

Left-Right Voting Records

Let’s start by looking at how liberal/conservative the candidates’ voting patterns were while in office. Political scientists have developed a scale for measuring the left-right dimension of voting, called the Nominate score. I ranked these scores by Congress, with 1 indicating the senator with the most liberal voting record, and 100 being the most conservative. [NB: Each Congress lasts two years, with the 1st going from 1789-1790, and so on from there. For our purposes, the relevant Congresses stretch from the 107th (2001-02) to the current 114th Congress (2015-16). Since the 114th isn’t over yet, its statistics should be correspondingly discounted relative to the others.]

As shown in the table below, the four candidates form almost perfectly symmetric mirror images of each other. Clinton was around number 15 during her four terms in the Senate, while Rubio was 85. So each of them, despite being tagged as the “establishment” or “moderate” candidates in the primaries, was each more extreme than the average member of their own parties. That is, Clinton voted in a reliably liberal direction, even more so than the majority of her Democratic colleagues, while the same holds true for Rubio vis-à-vis the Republican senators.

| Congress | State | Name | Rank |

| 107 | NEW YORK | CLINTON | 14 |

| 108 | NEW YORK | CLINTON | 15 |

| 109 | NEW YORK | CLINTON | 13 |

| 110 | VERMONT | SANDERS | 1 |

| 110 | NEW YORK | CLINTON | 15 |

| 111 | VERMONT | SANDERS | 1 |

| 112 | VERMONT | SANDERS | 1 |

| 112 | FLORIDA | RUBIO | 85 |

| 113 | VERMONT | SANDERS | 1 |

| 113 | FLORIDA | RUBIO | 86 |

| 113 | TEXAS | CRUZ | 100 |

The Candidates, Ranked by the “Liberalness” of their Senate Voting

(1: Most Liberal, 100: Most Conservative)

Sanders and Cruz also form a perfect pair of antipodes. Sanders had the most liberal voting record for each of his terms, while Cruz was the most conservative. As a note: the only time that a party’s nominee had the most extreme voting record in their party was George McGovern in 1972 –- draw your own conclusions.

The symmetry is broken, however, when you consider the states the candidates represent(ed). Vermont is by many opinion poll measures the most liberal state in the country, and Clinton’s rank almost perfectly reflects New York’s relative position as well. Cruz and Rubio, on the other hand, have voting records considerably more conservative than Texas (number 33 out of 50 in conservative opinions of its voters) or Florida (number 23 out of 50) residents, respectively.

Bill Passage

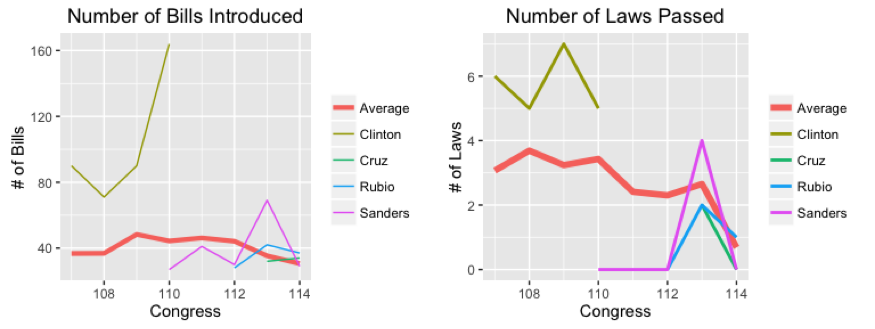

Voting analysis can give us clues to the kind of policies a president might pursue in office. But can they get legislation passed? The next two figures show the number of bills and amendments introduced by each candidate, and the number of those that eventually passed into law, along with the overall average for each Congress.

Note first that, although the average number of bills introduced has stayed more or less constant over time, the number actually passed has taken a nosedive in recent years. This reflects the increased partisan divisions in Congress, as well as the electorate, that have made Obama’s second term one where policy change may happen via executive actions or rulings in important Supreme Court cases, but rarely via the normal legislative route.

In terms of the various candidates, Clinton was by far the most active in terms of introducing and passing legislation; her totals are significantly above congressional averages for each of her terms in office. This makes sense in terms of her political history: Clinton entered the Senate in 2001 with a lot to prove — she had won just 15 of New York’s 62 counties in her 2000 election victory and wanted to establish herself as a legislator who could get things done. She worked hard, especially pushing programs that benefitted upstate New York’s more rural, agricultural economy, and was rewarded in 2006, winning re-election handily with a majority in 58 counties.

Sanders, on the other hand, has fewer legislative achievements to his name. He had a spurt of activity in the 113th Congress (2013-14), where, perhaps looking forward to his upcoming presidential bid, he introduced 69 measures, four of which passed into law. As noted above, Sanders has consistently represented his state’s liberal voters, but while the policies he has proposed may have been popular at home, in general they have not won sufficient support to be enacted into law.

Cruz and Rubio are about average in terms of measures introduced and below average for number passed. Neither, to date, has a major legislative initiative to their name. But see the next section, for Rubio’s record has more to it than it seems.

Co-Sponsorship

Actually passing policy means getting others to support your positions, and in today’s environment that entails getting members of the opposite party to vote in favor of your proposals, at least every once in a while.

Thus we now turn to analysis of cosponsorship trends. When a bill or amendment is introduced by a member of Congress — making them the “sponsor” of that measure — other members of their chamber can register their support for it by adding themselves as “co-sponsors.”

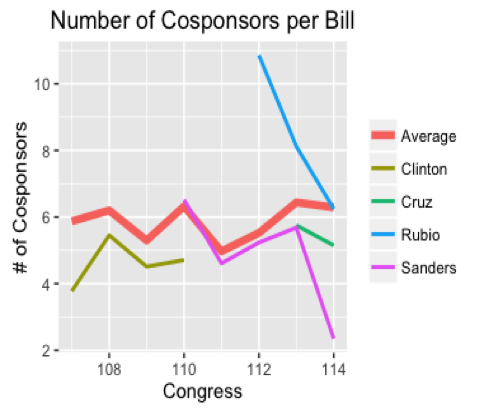

As the figure below shows, even though Clinton was far ahead of the others in terms of getting her bills passed into law, she did not have an especially high number of cosponsors per bill, on average. Neither did any of the other candidates, with the notable exception of Rubio in his first few Congresses.

As the chart shows, the few measures that he introduced in his first years in office were relatively high-profile, gaining the support of a number of colleagues. However, the efforts produced few results, one example being the immigration reform bill he introduced as a member of the bipartisan “gang of eight” after the 2012 elections. Thus Rubio’s time in the Senate — somewhat similar to his presidential campaign — started out with a flurry of activity but then faded out, as he failed to assemble coalitions to get behind his proposals.

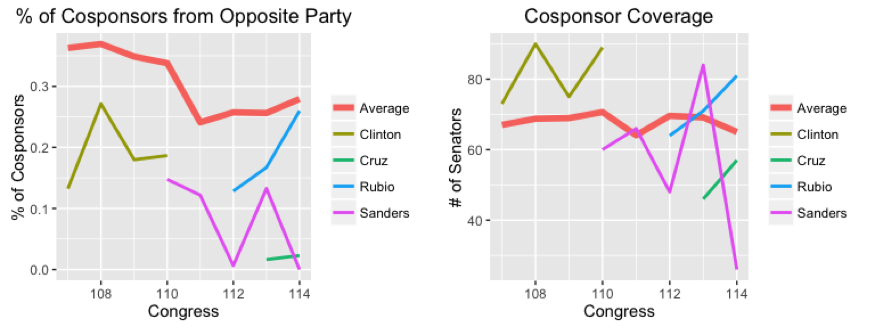

To measure the candidates’ track records of creating bipartisan coalitions, we look at two measures of their ability to attract the support of their colleagues from across the aisle. First, the percent of cosponsors who come from the opposite party. Second, a measure of “cosponsor coverage,” meaning the number of senators who cosponsored at least one measure proposed by the given candidate in the course of a single Congress.

All of the candidates perform a bit below average in the percent of cosponsors from the opposite part, with Clinton and Rubio again doing better than Sanders or Cruz. And in the coverage measure, Clinton is relatively high, with Sanders and Rubio close on her heels (except for the most recent Congress, where Sanders has almost no cosponsors for the measures that he has introduced). Cruz is especially low in coverage, gaining three Democratic supporters in his first term, and four in this, his second term. Of course, Cruz has spent his time in the Senate mainly working to oppose existing policies (via government shutdowns and filibusters) rather than create new ones, so this is not too surprising.

Conclusions

Of course, there has been one other sitting senator — the first since John F. Kennedy in 1960 — elected to the presidency, and that is Obama, who spend four years in the Senate prior to his election in 2008. (Nixon spent two years in the Senate before becoming Eisenhower’s VP, and Lyndon Johnson was a senator when he became Kennedy’s VP.) What would this analysis have said about him?

Obama’s voting record was a tad more conservative than Clinton’s — number 18 on the list compared to her 15 — but he also represented a slightly less liberal state than she did. He proposed an average of 68.5 bills each Congress, which is higher than average, but he only passed a below-average 1.5 bills per Congress. Thus Obama had a lot of ideas about what to do, but didn’t yet have the track record of being able to work with his fellow senators to bring these ideas to fruition.

Interestingly, Obama’s bipartisan measures are all average or above average compared to the other candidates, so while trying to garner support for his bills he was able to work with Republicans fairly well. This would probably have made it even more of a surprise when, once he took office, the Republican party as a whole refused to work with him in any fashion to pass his policy agenda.