Of course, the fiscal cliff is attracting a lot of attention (including by me). This is understandable, as it has been built up for two years, follows directly from the current partisan-cum-policy wrangling of the Democrats and GOP, and — most importantly — stars Barry O. and Johnny B. in a wacky “odd couple-meets-buddy film” romp through the fallow weeks of the NBA season.

But a much more sinister, almost art-film-esque drama is silently brewing and gaining steam in DC as well. The almost indecipherably and entirely incongruously-named “Alternative Minimum Tax Exemption Extension” issue remains unresolved. (Here’s a good succinct take on it.)

What is this dark horse, you ask? Well, the basics of taxation are hardly basic. The Alternative Minimum Tax, or AMT, is essentially a second tax system intended to tax the rich. (Here’s a nice description with some examples.) In an imperfect nutshell, the idea of the AMT is that you calculate your federal income tax the normal way, calculate your income tax according to the AMT and then pay the higher of the two (that’s the key incongruity of the naming system, in my opinion). The details are potentially very complicated, because the AMT is designed partly as a stop-gap protection against some of the tax code’s historically more-abused deductions (i.e., “loopholes”).

If you know anything about the AMT, you probably know that it is not “inflation adjusted.” Oddly, the AMT is pretty close to a flat tax (26% up to $175K and then 28% on the income over $175K). If that were “it,” inflation adjustment would be a truly minor issue. However, as you might expect, that’s not “it.”

Federal income taxes have three big components aside from rates and brackets. These are deductions, exemptions, and credits. Credits are simply refunds in another guise (though, while some can result in you paying negative taxes, most do not. In that case, a credit results in a refund only to up to the amount that you already paid in taxes in the first place). I will not discuss them in any more detail here, as they are not really related to this debate.

A deduction is an amount you reduce your taxable income by. A famous (and currently debated) example is the homeowner’s mortgage interest deduction. If you earn $75K and pay $10K in interest on your home mortgage, your taxable income (aside from other deductions, etc.) is $65K. Money spent on deductible expenses is often called “pre-tax money,” because in a real sense you get to pay it before it gets taxed.

Under the AMT one loses many common deductions and other’s homeowner’s mortgage. Many of these increase in nominal value with inflation, so there’s one implicit reason people refer to the AMT as not inflation adjusted.

More important for this debate is the exemption. In a nutshell, an exemption is a deduction that you get without spending any money. It’s kind of a catch-all allowance that reduces one’s taxable income. In the standard income tax system, a taxpayer gets an exemption equal to $3,800 for each taxpayer and dependent. (In addition, an individual gets a $5,950 standard deduction (couples get $11,900), which is essentially an exemption that one can take if one doesn’t claim (most) other deductions.) Under the AMT, on the other hand, the exemption is much higher. In 2011, it was $48,450 for an individual, and $74,450 for a married couple.

Note. Some day I might write about the astonishing “marriage penalty” contained in the AMT (the first hint: 2 x $48,450=96,900>74,450.). For now, simply note that when I say “married” below, I technically mean “Married, filing jointly,” because I have no idea why one would do otherwise if you knew your were going to pay the AMT.) In addition, I am not going talk here about the “rolling back” of the exemption, but it does figure where appropriate into some calculations at the end of the post. (shut up. – ed.)

Calculating AMT. So, to keep it simple, let’s just call the AMT a 27% flat tax on income after the homeowner’s interest deduction and the exemption. Then, one’s AMT is essentially

AMT = 0.27 (Income-Mortgage Interest-$48,450) if you’re single, and

AMT = 0.27 (Income-Mortgage Interest-$74,450) if you’re married.

…Of course, in reality things are a little more complicated, but I’m trying to make a simple point here. (too late – ed.)

But…WHAT IS THE ALTERNATIVE MAXIMUM CLIFF?!? Ahh, yes. “The Alternative Maximum Cliff” is approaching because the 2011 level for the exemption was the result of an extension passed by Congress that expired at the end of 2011, returning the exemptions to $33,750 for individuals and $45,000 for couples. So…the current AMT is

AMT = 0.27 (Income-Mortgage Interest-$33,750) if you’re single, and

AMT = 0.27 (Income-Mortgage Interest-$45,000) if you’re married.

The biggest tax increase as a result of non-extension of the exemption will be for a married couple making about $350K a year. And, no, nobody should cry for such people. (That’s why this is kind of shocking – ed.) Such a married couple faces a tax increase — even holding the Bush tax cuts fixed and assuming the fiscal cliff is completely delayed — of $7,951.50. That’s a 2% tax increase in terms of their actual income.

The final and even more important point about this is as follows. The couple I just described was almost certainly paying AMT last year, too. However, if Congress does not extend the exemption, the number of people who owe AMT will jump enormously. In particular, the exemption is used to calculate AMT tax liability, and you owe the AMT if your AMT tax liability is higher than your standard tax liability. So, a drop in the exemption potentially affects every individual or married who earns moderately high incomes.

But, “Will the (new) AMT affect me?” Here’s a highly approximate answer for most people. This is for the new system if there is no extension—if there is an extension, the system will likely be almost the same as last year’s, so your status from last year return is a good (but imperfect) guess about this year’s.

Denote your gross income by Y. Add your standard exemptions under the regular income tax system (for a family of four, this is $15,200) to your state and local income taxes. Denote this amount by X. Then, check my Jeff Foxworthy-esque “if-thens” below:

If you’re married, then

If Y < $150,000 and X > $48,600 – 0.08 * Y, then you might owe AMT.

If $150,000 < Y < $450,000 and X > $71,280 – 0.35 * Y, then you might owe AMT.

If Y > $450,000 … then “why, you might go screw yourself.”

If you’re single, then

If X > $112,500 and X > $36,450 – 0.08 * Y, then you might owe AMT.

If $112,500 < Y < $247,500 and X > $66,825 – 0.35 * Y, then you might owe AMT.

If Y > $247,500 … well, you know.

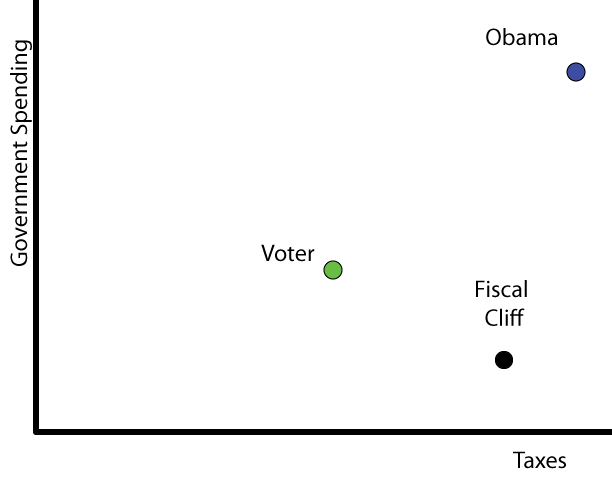

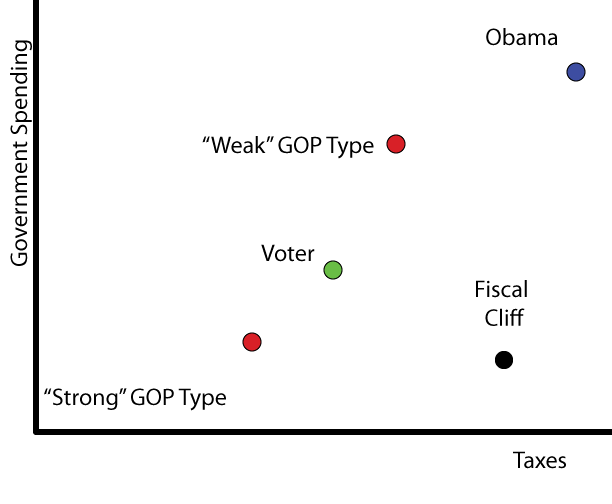

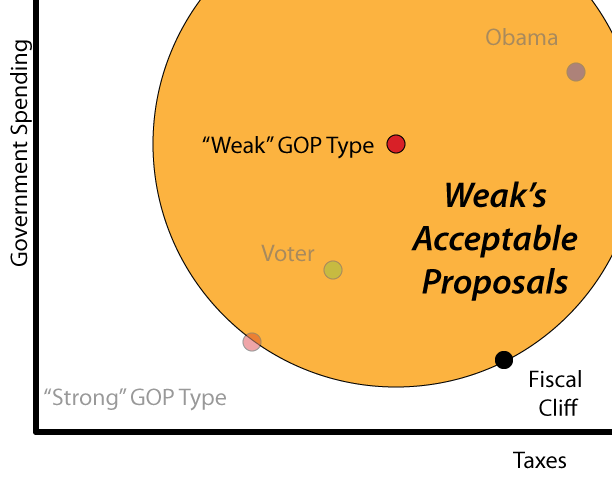

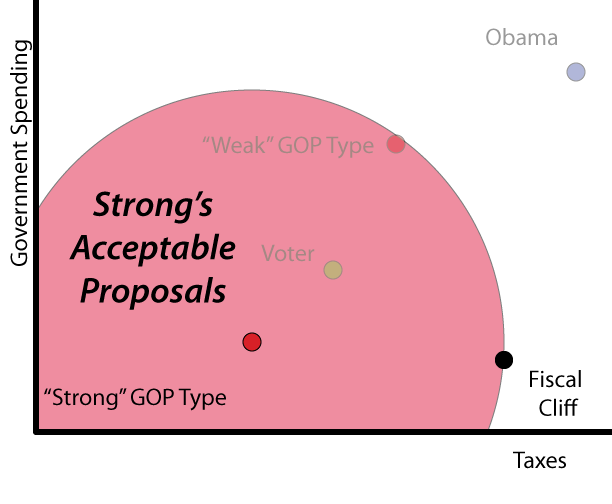

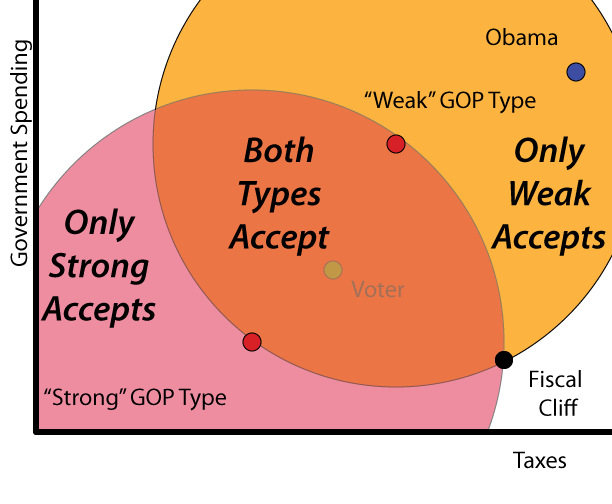

What’s the politics of this? Well, the confluence of this “opportunity” and the fiscal cliff is interesting. Essentially, if Congress wants to play by its budget accounting rules, it can do so more easily by allowing the exemption extension to expire. Call it the Triple-Ex budget trick. I just came up with that. So…time to retitle this baby and sign off, leaving you with this.

Like this:

Like Loading...